Madagascar Colonization: A Journey Through History, Resistance, and Legacy

Introduction

Madagascar, the fourth-largest island in the world, is a land of unparalleled biodiversity, vibrant cultures, and a history shaped by waves of migration, trade, and conflict. While its unique ecosystems and lemurs often steal the spotlight, the island’s colonial past remains a critical chapter in understanding its modern identity. From early settlements by Austronesian voyagers to French colonial rule, Madagascar’s story is one of resilience and adaptation. This article explores the colonization of Madagascar, delving into its pre-colonial history, the reign of its infamous “Mad Queen,” and the lasting impacts of European imperialism.

The History of Madagascar: From Settlement to Sovereignty

Early Settlement and Kingdoms

Madagascar’s human history began around 2,000 years ago when Austronesian seafarers from Southeast Asia crossed the Indian Ocean, followed by Bantu migrants from East Africa. These groups merged over centuries, creating the Malagasy people and their unique cultural tapestry. By the 7th century, Arab traders established coastal settlements, introducing Islam and writing systems.

By the 16th century, powerful kingdoms like the Sakalava, Betsimisaraka, and Merina emerged. The Merina Kingdom, based in the central highlands, rose to prominence under King Andrianampoinimerina (1787–1810), who unified much of the island through diplomacy and conquest. His son, Radama I, expanded the kingdom further, opening Madagascar to European trade and missionaries.

European Contact and the Age of Exploration

European interest in Madagascar began in the 1500s, with Portuguese, French, and British ships vying for control of its strategic ports. The island became a hub for the spice trade and, tragically, the slave trade. By the 19th century, Britain and France competed for influence, signing treaties with Merina rulers. However, European ambitions collided with Malagasy sovereignty, setting the stage for conflict.

The Mad Queen of Madagascar: Ranavalona I

One of the most polarizing figures in Malagasy history is Queen Ranavalona I (1828–1861), often dubbed the “Mad Queen” by European chroniclers. Ascending the throne after her husband’s death, she reversed her predecessor’s pro-European policies, viewing foreign influence as a threat to Merina culture and independence.

- Resistance to Colonialism: Ranavalona expelled Christian missionaries, outlawed Christianity, and executed Malagasy converts. She famously declared, “Let neither industry nor agriculture be introduced here; let the knowledge of the white man be avoided as a deadly poison.”

- Isolation and Autocracy: Her reign saw forced labor, political purges, and harsh penalties for dissent. While her policies preserved Malagasy autonomy temporarily, they also isolated the island technologically and economically.

- Legacy: Though demonized by Europeans, modern historians recognize Ranavalona as a fierce defender of sovereignty. Her resistance delayed formal colonization by decades but left the kingdom vulnerable to future European aggression.

The Scramble for Africa and French Colonization

Prelude to Colonization: Treaties and Tensions

After Ranavalona’s death, her successors reopened Madagascar to European powers. France, seeking to expand its empire, signed the Lambert Charter in 1855, granting it economic privileges. By 1883, tensions erupted into the First Franco-Hova War, ending with Madagascar ceding the northern port of Antsiranana (Diego Suarez) to France.

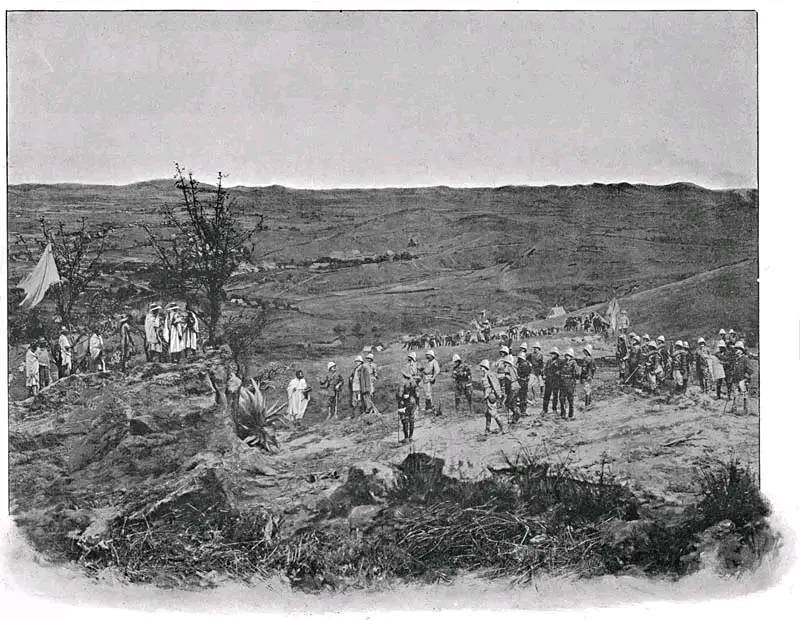

The Franco-Hova Wars and Annexation

The Second Franco-Hova War (1894–1895) marked the end of Merina rule. French forces bombarded Antananarivo, forcing Queen Ranavalona III to surrender. In 1896, Madagascar was declared a French colony, and the Merina monarchy was abolished in 1897.

Colonial Administration and Economic Exploitation

Under French rule, Madagascar became a source of natural resources. The colonial government:

- Introduced cash crops like coffee and vanilla

- Built railroads and infrastructure to serve export economies

- Enforced the corvée system, coercing Malagasy labor for public works

- Suppressed local culture, promoting French language and Catholicism

Resistance persisted, notably the Menalamba Rebellion (1895–1898), where peasants and nobles rebelled against forced labor and land confiscation.

Resistance and the Road to Independence

Early 20th Century Nationalism

Malagasy nationalism grew after World War I, with figures like Jean Ralaimongo advocating for civil rights. The brutal 1947 Uprising, which saw 11,000–100,000 Malagasy killed by French forces, became a catalyst for independence.

Independence Achieved

In 1960, after decades of activism, Madagascar peacefully gained independence under President Philibert Tsiranana. However, the transition retained French economic influence, sowing seeds for future political strife.

Legacy of Colonization in Modern Madagascar

Colonization reshaped Madagascar’s trajectory:

- Cultural Hybridity: Malagasy language blends Austronesian roots with French, while Christianity coexists with traditional beliefs

- Economic Challenges: Extractive policies left a legacy of poverty and underdevelopment

- Environmental Impact: Deforestation and resource exploitation accelerated during colonial rule, threatening endemic species

Today, Madagascar grapples with balancing preservation of its heritage with the demands of globalization—a tension rooted in its colonial past.

Conclusion

Madagascar’s colonization story is a testament to the resilience of its people. From the defiant reign of Queen Ranavalona I to the scars of French rule, the island’s history reflects both the brutality of imperialism and the unyielding spirit of resistance. As Madagascar navigates post-colonial challenges, understanding this past remains vital to forging a future rooted in sovereignty and cultural pride.